Video:

https://www.indystar.com/videos/sports/2018/04/11/watch-sugar-ray-seales-story-boxing-all-its-beauty-and-brutality/33740247/

SEVEN SURGERIES, $100,000 IN DEBT, A DINGY EAST-SIDE GYM: WHY SUGAR RAY SEALES STILL NEEDS BOXING

Zak Keefer, zak.keefer@indystar.com

Published April 12, 2018

Like most days, the champ needs to bum a ride, so he slides into the front seat and spills his affection for the sport that stole his sight and emptied his pockets. Strange thing is: He’s happy to. His words come in a hurry, his raspy voice dancing across three decades in the ring. “I almost killed two guys with 10-ounce gloves,” he brags at one point. “They just laid there for 20 minutes. We thought they were done.”

Done as in dead?

He nods. “Done as in dead.”

The champ could ramble on, all day, all night, probably all month, not about pummeling a pair of opponents to within inches of their life — thankfully — but it. The Game, he calls it. The era. The stakes. The glory. The pain. All that. Boxing left the man broke, left the man blind, but somehow it never left the man bitter. All Ray Seales wants anymore is someone who’ll listen.

“You missed the turn,” he points out a few minutes later. He’s right. He can’t see 10 feet in front of him; damned if he doesn’t know where his gym sits, the gym on Indy’s east side that desperately doesn’t want to be found. It’s hiding off Washington Street, sitting there with no signs, no windows, no nothing, a building so beat up it looks as if it’s been abandoned 20 years. Step through the back door, though, and it all makes sense: the stench of sweat, the sputter of the speedbag, the smack of jumping rope, the scratchy speaker belting out rap music. It’s dark and dingy, cluttered and cramped. It’s perfect.

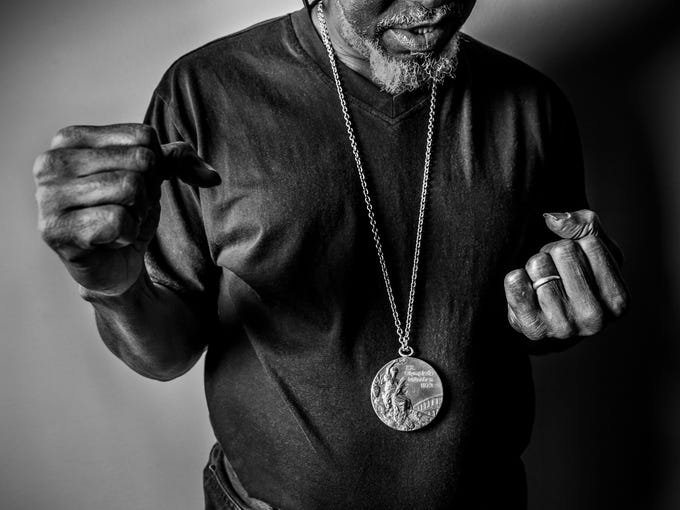

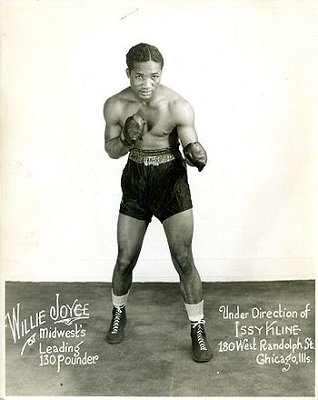

Sugar Ray Seales won gold at the 1972 Munich Olympics. He carries the medal in his pocket everywhere he goes. Later in life, he was thumbed in the eye during a fight, eventually leading to the end of his career. He found himself in $100,000 debt.Mykal McEldowney/IndyStar

The champ hobbles in like he owns the place. “This is where I get my fix,” he beams.

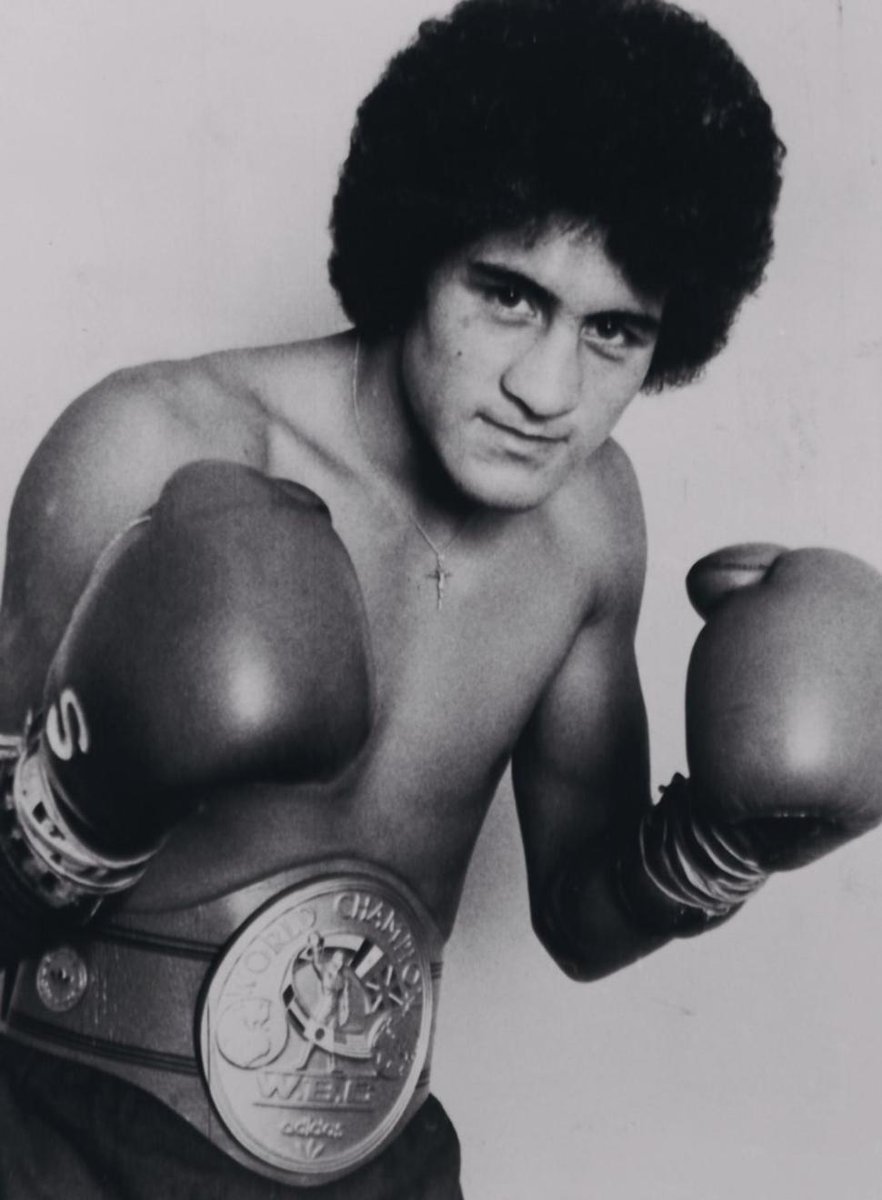

There’s one poster in the whole joint, pinned to the back wall. It’s him. It’s a young Ray Seales, the fighter they called Sugar, sleek and slender and in his prime, ready to take on the world.

That was 40 years ago, before the lights went out and the money dried up. These days his beard is graying, his glasses thick as a quarter. Everything changed after a fighter named Jamie Thomas popped him one night in Baton Rouge, detaching his retina, leaving him with an eye drenched in blood. “He took me out of The Game, and I still knocked him over the top rope,” Ray says, still hot about it four decades later. His vision — at first, completely lost — has trickled back. The left eye’s still dark, the right foggy. Some days, he’ll stumble into a punching bag he never sees. To read his phone, he holds it an inch from his face. He can’t see well enough to drive, so he begs the teenage fighters he trains to give him a lift.

There's just one poster on the walls of the Eastside gym Ray Seales coaches at. "When I started coaching here, they put that up," he said.

"You gotta work and believe if you want to be great."

(Photo: Mykal McEldowney/IndyStar)

His story is boxing in all its beauty and brutality, stirring one minute, sobering the next. The sport made Ray Seales, then it broke him. He’s 65 years old, seven eye surgeries deep, damn near blind, bumming rides to this dark and dingy gym so he can train fledgling fighters who can’t afford to pay him a dime. And yet he still loves it. Still needs it.

“I can see better in here,” he explains, sitting in the gym one afternoon, lacing up the same pair of tattered Adidas he donned for Team USA in the 1972 Summer Olympics. “Because this is where I belong.”

From there Sugar rises — time to work, time to teach. He bounces from fighter to fighter. “Ride the bicycle,” he barks to one — keep your feet under you. “Don’t cheat yourself,” he says to another — finish your punch. He’s an aging, wrinkled champ forever fueled by The Game. It’s his oxygen. Hardly anyone outside this gym knows his story. Hardly anyone in this city knows his name. Ray pays no mind to it. Ask him if he ever won anything big, and he’ll smile, and he’ll dig into his right pocket and pull out his answer. That’s where he’s kept his Olympic gold medal every single day since he won it 46 years ago.

The gym. The grocery. The movies. He literally takes the thing everywhere.

“It’s like my American Express card,” he likes to say. “I never leave home without it.”

In the back of his mind he knows it’ll all catch up to him — the residue of a million blows to the head, of some-400 fights. He sees what’s happening to former NFL players, to old fighters like himself. It’ll get worse, maybe soon. He suspects his mind won’t be right forever.

“It’s coming, it’s coming,” he sighs, sounding like a fighter stuck in the seventh round who knows the knockout is coming in 10.

“That’s why I have to pass on everything to the next generation now. So one of them can become champ like I was.”

Seales boxed for 19 years, had 430 fights with 200 knockouts and 19 losses...

When the bullies made fun of his Caribbean accent on the playground, he learned to drop them. Ray was 10 when his family moved from the U.S. Virgin Islands to Tacoma, Wash. “You laughing at me? Laugh at this,” he says, clenching the weathered fists that leveled those playground bullies, then won him 408 fights across his career.

He was 19 when the terrorists threatened to derail his dream. The Olympics were about to be cancelled, so Ray grabbed his suitcase and started packing for home. He could stand on the balcony of his hotel room and see members of Black September across the courtyard, rifles in hand, holding 11 Israeli athletes at gunpoint. He was 4-0 at that point, one win from gold. He thought it was over. Then the phone rang.

“When our coach called and told us the games were going to continue, I decided I wasn’t leaving without that gold medal.”

A sweeping uppercut, Ray’s iconic Bolo punch, flattened his Bulgarian opponent in the second round of the gold medal match. He won on points. The boy who’d learned to fight to fend off bullies left Munich as the only American boxer with a gold medal. He and his parents celebrated with cake and ice cream.

He turned pro. He fought all over the country. By 31, he’d lost vision in both eyes; by 33, he’d filed for bankruptcy, “so poor,” the judge wrote then, “that he couldn’t even pay the bankruptcy filing fee.” Those seven eye operations dug Ray a $100,000 hole his meager bouts could never lift him out of. Doctors ordered him to stop fighting. He refused. “The man upstairs was telling me, ‘No more, no more,’ and I always told him, ‘Just one more, just one more.’”

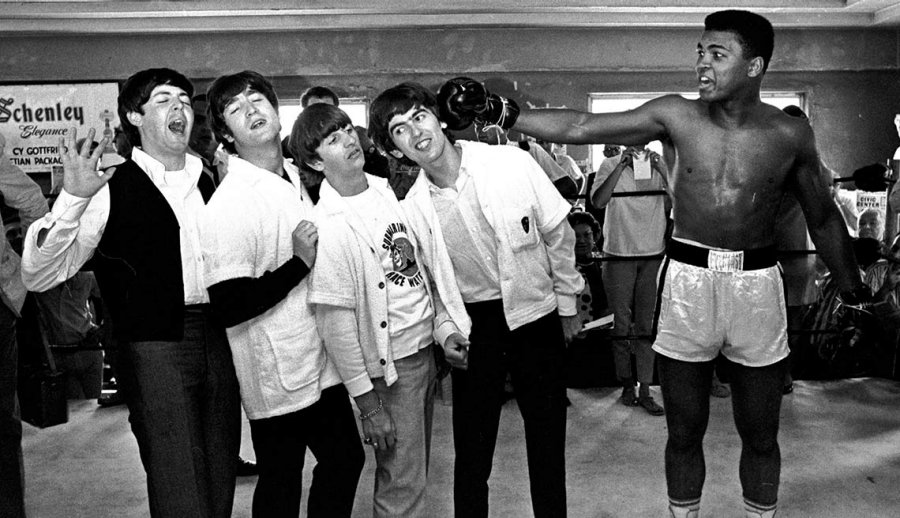

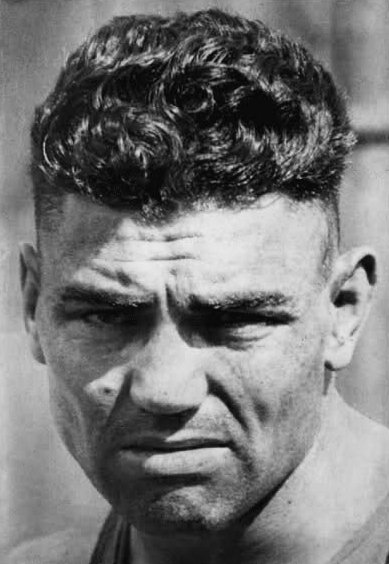

The great Muhammad Ali stopped by Seales' gym in Tacoma, Wash., one afternoon. "He punched the bag so hard it came off the wall," Ray remembers.

(Photo: Mykal McEldowney/IndyStar)

He borrowed money from friends for medication. Doctors claimed he memorized the eye charts so he could pass the exams and keep fighting — a charge Ray denies. What he doesn't deny is opponents swinging at his eyes late in his career, knowing with one punch they could send him straight into darkness.

He fought to the bitter and bloody end.

Along the way he had a blast. He partied with Evel Knievel (“He taught me how to drink Wild Turkey!” Ray says), trained with Muhammad Ali (“He showed up at our gym and punched the bag so hard it came off the wall”) and became a national middleweight champion. “Four-hundred and thirty fights,” Ray says. “I had 19 losses.” He never became a household name, never became as celebrated as the fighter who shared his nickname, Sugar Ray Leonard. Instead, Ray was the Southpaw who became a stepping stone — the foe title contenders were told to bury on their way to the top.

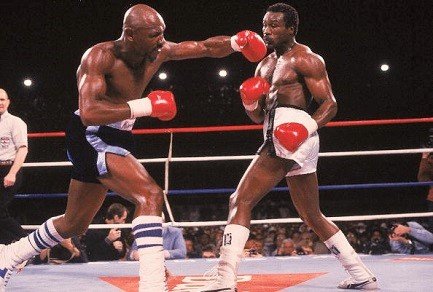

The problem was he never made any real money. Ray says his going rate back then — even as an Olympic champ — was $50 a round. He was working with a small-time manager, he says, a local businessmen from Washington who ran a chain of taco joints and managed boxers on the side. When Ray finally did get his shot, “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler stopped him cold. When the eye issues arose in the early 1980s, Ray burned through his savings.

Then his friends came to help.

“He’s got the three B’s,” Sammy Davis Jr. said of Seales at a 1984 benefit for the fighter. “He’s black, he’s blind, and he’s broke.” On hand that night were boxing royalty: Hagler, Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini, even the great Ali. The event raised enough to pay off Ray’s debts.

As boxing faded into the background, and Ray’s vision slowly inched back, he found work teaching students with autism in the public schools around Tacoma. He did that for 17 years before he and his wife, Mae, landed in Indianapolis to be closer to her family. Retired and restless, Ray started looking for a boxing gym.

He needed to coach.

Jamar Lee is an 18-year-old senior at Warren Central who drives out of his way three times a week to give the aging champ a ride to the gym. Coach Ray works him, works him hard. “He’s one of the reasons I’m still here,” Jamar says.

Pat McPherson is the IMPD cop who runs Indy Boxing and Grappling in his spare time, the tiny gym on the city’s east side that refuses to charge any kid who comes through its door. He met Ray a few years back and gave him a key to the place. “He just started coming every day,” Pat says.

One fighter who calls the gym home — Frank Martin, Indiana’s first national golden gloves champ in three decades — has turned pro. But most are teenagers, learning The Game from scratch. Some are just trying to stay off the streets. None has a clue he's about to work with an Olympic gold medalist.

Sugar Ray Seales hands his 1972 Olympic gold medal to Nick Culley, of Rushville, Ind., during a Golden Gloves bout at Tyndall Armory on Thursday, March 29, 2018. Seales has carried his medal in his right pocket everyday for 46 years.

(Photo: Mykal McEldowney/IndyStar)

“In today’s society where it’s all about what you’ve done for me lately, we lose sight of the treasures that are around us,” Pat says, nodding at the poster that hangs on the back wall of his gym, a young Sugar Ray Seales ready to take on the world.

“Sometimes, the treasure is right in front of us.”

Ike Boyd runs the gym with McPherson, coaches Martin, and travels the country with Ray for tournaments.

“We got a (expletive) Olympic gold medalist in our midst,” Boyd says. “We got kids coming in here from all over, from all different situations. You wanna talk about inspiration? The guy’s got a gold medal in his pocket!”

Ray calls his medal “the people’s medal,” pulling it out a dozen or more times each day to share it with anyone who asks. When he and his wife moved into a retirement home on the Northside, he passed it around the cafeteria. When he attends the Indiana Golden Gloves tournament at Tyndall Armory, he places it around the neck of every youngster who approaches. He’s had the thing almost 46 years now. Never put it in a safe once. Never needed to.

His right pocket has done just fine.

“And when I die,” Ray says, “it’s going to my grandchildren.”

To know Ray is to see him in his element, inside the shabby gym, working with the young fighters, bumping into punching bags he never sees, then continuing to teach.

They respect him inside these walls. They listen to him here. Anymore, that’s all the aging champ wants. Tattered Adidas on his feet, gold medal in his pocket, sputtering speedbags in his ear.

“What’s better than this?” he says. “What’s better than this?”

Call Star reporter Zak Keefer at (317) 444-6134 and follow him on Twitter:

@zkeefer.

You’ve Never Seen Luxury Like This on a Cruise - Research Luxury Med CruisesYAHOO! SEARCH

You’ve Never Seen Luxury Like This on a Cruise - Research Luxury Med CruisesYAHOO! SEARCH Male Wet'suwet'en Chiefs Strip Female Chiefs of Title Over Coastal GasLink Pipeline SupportTHE GLOBE AND MAIL

Male Wet'suwet'en Chiefs Strip Female Chiefs of Title Over Coastal GasLink Pipeline SupportTHE GLOBE AND MAIL Dealers Cashing Out On 2018's Cars That Didn't SellWWW.DISCOUNTDRIVERS.COM

Dealers Cashing Out On 2018's Cars That Didn't SellWWW.DISCOUNTDRIVERS.COM 20 Rudest Countries (USA Is Lower Than You’d Think)ALOT TRAVEL

20 Rudest Countries (USA Is Lower Than You’d Think)ALOT TRAVEL