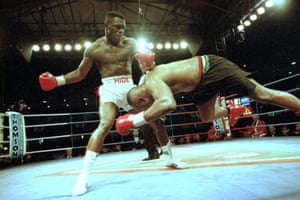

Michael Bentt beats Tommy Morrison to become a world champion. Photograph: Mark Morrison/Getty Images

The former WBO heavyweight champion,

Michael Bentt, is taking a break from writing a screenplay. He expresses himself on stage and screen as an actor and director these days, but thoughts of his life in boxing are never far from his mind. “My earliest memory as a young kid growing up in Queens was Muhammad Ali fighting in Germany. My dad was a huge admirer of Ali, or Cassius Clay as he insisted on calling him. He wanted a mascot who would become the next Ali and, unfortunately, I was that mascot.”

Bentt was born in London and grew up in a middle-class suburb of New York with a boxing-obsessed father who was intent on creating a champion, whether or not his son had any interest in the sport. Bentt’s father had built a reputation as a fierce street fighter on the streets of Kingston, before emigrating from Jamaica to the US to make his fortune. “Where I grew up was a decent and affluent place but some horrible stories went on behind those manicured lawns and nice cars. The niceness could be a mask.”

Bentt began fighting regularly in amateur contests aged nine, winning some and “getting tuned up” in others. He was academically gifted and a keen reader, but was also becoming more fluent with his fists. Despite his natural ability, the sport was never a natural fit and, after a year in the ring, he finally plucked up the courage to tell his father that his nascent boxing career was over. “I went to school, thought about it all day and resolved to tell dad I wanted out. I said: ‘Dad, I don’t want to box anymore.’ He went ballistic. When someone opposed his masculinity, it was time to clear out. He went over to our black and white television, broke off the antenna and did a number on me.”

Advertisement

Bentt took a vicious beating that day, but he also won a precious victory by standing up to his father. He went on to become one of the US’s most decorated amateur boxers ever but always had a complicated relationship with the sport. “I still had a fascination with boxing, I just didn’t want to get hit. I was becoming a chronic truant at school. I would go into the school library, pick out some books and ride the subway all day reading them.

“One day I read in the New York Daily News about boxers representing the United States who had perished in a plane crash in Poland. One of the boxers who died was a fighter who had shown me kindness and was really my first mentor. I decided to fight on for him, even though the whole time my father thought I fought because of his enthusiasm for boxing.”

After just missing out on qualification to the Seoul Olympics after a defeat to eventual gold medallist Ray Mercer, Bentt returned home determined to hang up the gloves. However, interest from a legendary trainer pulled him back in. “I was flying back from the trials in San Francisco and a teammate told me he was signing with Emanuel Steward and that he could put in a good word for me. I had no interest but Emanuel drove up to our house and wanted me to sign. He and my dad got on so well. They were both larger-than-life personalities. My dad had built a huge amount of resentment at me not making the 88 Olympics and this was my ticket out, so I said: ‘Let’s sign.’”

Michael Bentt is beaten by the count as he loses his world title to Herbie Hide in London in 1994. Photograph: John Gichigi/Getty Images

Bentt was an exceptional amateur but he was not accustomed to the hard atmosphere among the pros at Steward’s dank basement gym in Detroit. He had grown up in relative comfort and was used to high-quality training facilities in the US boxing team, so the Kronk Gym came as something of a surprise. “I’m a kid from the suburbs and the culture there just bred hunger in the fighters like a disease. They were hard people and it was hardcore within that gym, although some of the champions were sweethearts. I didn’t really like it. I just tried to put on the blinkers and train.”

Bentt made his professional debut in February 1989 against outside prospect Jerry Jones at Trump’s Castle in Atlantic City. The fight was shown live on ESPN and he was knocked out in the last second of the first round. Bentt never returned to Detroit, or the Kronk Gym, and instead took a job in a hospital. He was grateful for the work but “just didn’t belong”. Long after the physical bruises had healed, he remained fragile and that pain was exacerbated when he found a note on his car from a stranger mocking him for the knockout against Jones.

The psychological effect of that defeat is explored in the first episode of the

Netflix documentary series Losers. The film shows a boxer who felt he had not only lost a fight but his own masculinity, which had always been framed by boxing and his father. “I was terrified, to be honest, after that defeat. I didn’t want to see anyone. I was working but managed to blow all of my money. Then I would drink. Then I thought I should work out and I sparred with my brother at the gym. It got competitive, like it can do with brothers, then I floored him. I started crying and didn’t go back to boxing for another 18 months.”

Bentt made his way back to boxing as a sparring partner for

Gary Mason and then Evander Holyfield. Away from the tyranny of his father’s mental warfare and the expectation of his televised debut, Bentt thrived. “One day Evander’s trainer said to me: ‘Goddamn babycakes, when you fuck around and spar with Evander, I can’t tell who the champion is.’ That was priceless. I took those words with me wherever I went.”

He realised he had more to offer and won his next 10 fights, putting him in line for a showdown with WBO champion Tommy Morrison. Even after this run of victories, he still doubted his decision to keep fighting. “I was still conflicted with professional boxing. It was a mind-fuck. You realise your father will only love you if you get punched in the face in public for a living. That’s a real psychological issue. I used the contempt I had for my father and it was valuable in the ring. If I didn’t have that contempt for my father, I would never have beaten Tommy Morrison.”

Michael Bentt falls to defeat against Herbie Hide at the Den in London.

Photograph: Sean Dempsey/PA

Bentt upset the odds and

stopped Morrison in the first round to become a world champion. Even with the belt tied around his waist, he still felt conflicted. “After the fight I didn’t want people telling me I was great. I had seen it all after my first fight, when there was nobody there. Then, after I won, there were 10 people waiting to congratulate me in the dressing room, congratulating each other. I wondered: where would all these have people have been if I lost? I recognised the hypocrisy.”

Bentt would soon find out. In his first title defence, he suffered a brutal knockout against Herbie Hide in London and woke up in hospital. His tumultuous and torturous relationship with boxing was over.

Again, he found solace in reading and writing. His natural gifts as a communicator eventually opened up a new career far from the ring, as an actor and director who has worked with Will Smith, Michael Mann, Clint Eastwood and Johnny Depp. He is probably best known for playing Sonny Liston in

the film Ali.

Bentt at the premiere for the Michael Mann film Public Enemies in 2009.

Photograph: Alamy

“Today I’m living between LA and Atlanta and I’m still a full-time actor and director. It’s been a long experience to get to where I am but I’ve found it incredibly gratifying. I have experiences that will last with me forever. Clint Eastwood told me I know what I’m doing when he was directing me; and Michael Mann, who doesn’t smile for anybody, winked at me during a take. I have this tough Jewish acting coach and, when you nail a scene, he hits the table three times. When I nail a scene, it’s honestly better than sex.”

Is nailing a scene better than winning a world title? “I’m appreciative of what the boxing game gave me and I’m appreciative that I survived but, when I’m on set now, there’s nowhere on this Earth I’d rather be.”