Don King, on Mike Tyson

"Why would anyone expect him to come out smarter?

He went to prison, not to Princeton."

"To me, boxing is like a ballet, except there's no music

and the dancers hit each other."

Saturday, November 30, 2019

Loaded gloves: the dark story of Luis Resto and his illegal fists

Loaded gloves: the dark story of Luis Resto and his illegal fists

https://www.theversed.com/10494/loaded-gloves-the-dark-story-of-luis-resto-and-his-illegal-fists/#.ePiEnJ3f98

https://youtu.be/kEVdywAtk50

On June 16, 1983 Luis Resto lined up against the undefeated prospect Billy Collins, Jr. at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The fight was the undercard for a bout between Roberto Durán and Davey Moore. What was supposed to be a sideshow to the Durán/Moore encounter, became an assault with a deadly weapon; the end of Billy Collins Jr’s career, and the start of a prison sentence for the disgraced Resto.

Luis Resto was born in Juncos, Puerto Rico, and moved to the Bronx when he was nine years old. His first taste of boxing was pugilistic to say the least; late in his eighth grade year, he elbowed his math teacher in the face, and spent six months in a rehabilitation center for the mentally disturbed. Fortunately for Luis, an uncle decided to sign him up for boxing lessons in a Bronx gym, and the rest is history.

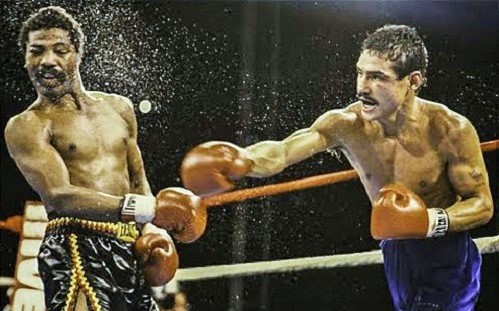

Luis Resto punches Billy Collins Jnr,. Source : All Things Crime

Resto matured into a competent amateur, winning both the 1975 and 1976 147 lb Golden Gloves Open Championships. He turned pro in 1977 and proceeded on the journeyman path, managing a fairly unremarkable 20-8-1 record after six years on the road.

His light-punching style, coupled with the undefeated credentials of his opponent Billy Collins’ Jnr., promised to make this a one-side, uneventful evening. 10 rounds later and the fight is over. Collins’ eyes are swollen shut; Resto has tampered with his gloves. The alarm was raised by Collins’ father and trainer, Billy, Sr., who shook Resto’s hand. Screaming that he thought the gloves had no padding, Collins, Sr. demanded that the New York State Athletic Commission impound the gloves. An investigation discovered that an ounce of padding had been removed from each glove, the barroom equivalent of using a knuckleduster. To think Collins’ was subjected to 10 rounds of this is bad enough–it would later emerge that Resto’s wraps had been hardened in plaster of Paris.

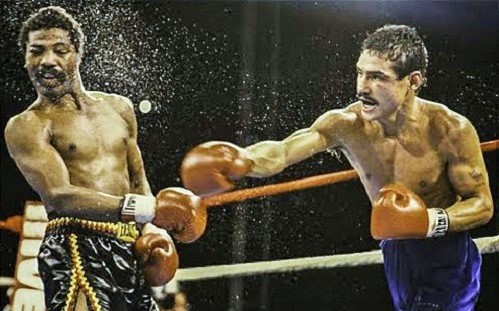

A macabre image of a battered Billy Collins, alongside Luis Resto. Source : Jeff Pearlman

After a month’s investigation, the New York State Boxing Commission determined that Resto’s trainer, Panama Lewis, had removed the padding from Resto’s gloves. The commission suspended Resto’s boxing license for at least a year, stating that Resto should have known the gloves were illegal. Collins, who suffered a torn iris and permanently blurred vision, would never fight again. His career was over and he fell into a downward spiral. He drove his car into a culvert while intoxicated and died a few months after the fight–his father would later speculate that this was a suicide.

Resto’s trainer, Panama Lewis, pictured in 1982. Source : Alcherton

In 1986, Lewis and Resto were both put on trial and found guilty of assault, criminal possession of a weapon (Resto’s hands) and conspiracy. Prosecutors argued that Resto must have known his gloves were illegal, and therefore the bout amounted to an illegal assault. Prosecutors also argued that the plot was centred on a large amount of money bet on Resto by a third party, who had met with Lewis prior to the fight.

‘It was like a bare knuckle fight,”

Eric Drath, Director of “Cornered.”

Resto served two and a half years in prison, and stood by his innocence for almost a quarter-century. However, in 2007, Resto admitted to Collins’ widow, Andrea Collins-Nile, that he had known about the padding, as well as confessing to the use of plaster on his wraps. Resto said he didn’t protest at the time even though he knew it was wrong. “At the time, I was young,” he said. “I went along.”

Robert Mladnich last reported on Resto’s whereabouts in 2008. He was living in an apartment near the gym where he once trained. Billy Collins Jr. died before his 23rd birthday. No doubt a large part of Resto died that evening, but his decision to hide behind a vale of naivety will condemn him till the end; he was 28 when this cowardly act took place.

George Mackenzie

Editor

Part-time work as Tuvalu's World Cup correspondent.

Aaron PRYOR vs. Alexis ARGUELLO I | FULL FIGHT HIGHLIGHTS

https://www.thefightcity.com/pryor-vs-arguello/

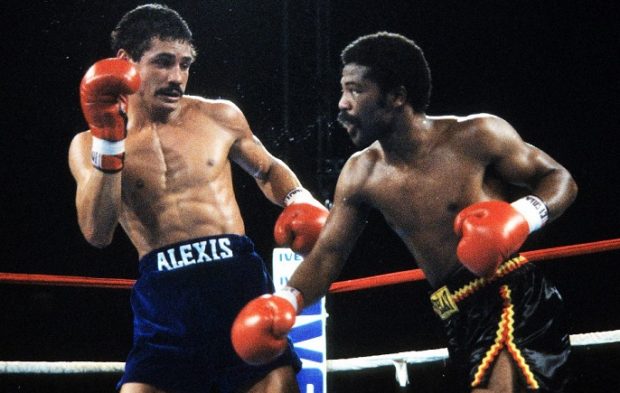

It’s November, 1982 and the sport of boxing is bigger than ever. Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns are all mainstream stars and fight fans enjoy championship matches on free cable TV almost every weekend. Rocky III is a huge hit in theaters and just a few months previous, one of the richest fights of all-time had taken place, Larry Holmes vs. Gerry Cooney. And standing right in the thick of things, not yet a boxing superstar but certainly one of the higher profile champions: Alexis Arguello.

A regular on network television, the Nicaraguan is regarded as not only one of the best boxers on the planet, but an all-time great, only the seventh fighter in the long history of boxing to win three divisional world titles. And that’s what the big battle in Miami’s Orange Bowl was all about: to see if Arguello could make history and emerge as a true immortal, a sports superstar, by becoming the first boxer ever to win world titles in four different weight classes.

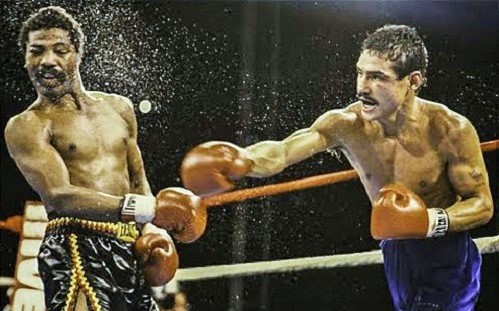

Arguello’s chief threat was his powerful right.

The man Arguello had to beat to get that fourth belt was not a household name, but everyone in the game knew Aaron “The Hawk” Pryor was one hell of a fighter. In contrast to popular champions like Leonard and Hearns, Pryor’s whole career had been a struggle for recognition. An outstanding amateur talent with over 200 wins, he dropped a close decision to Howard Davis Jr. in a critical match and so failed to make the team that won a boatload of medals at the ’76 Olympics. Without the fame a gold medal would have brought him, Pryor soon discovered the public was not particularly anxious to buy tickets to his fights.

While some might have been discouraged by this, being the outsider was nothing new for Pryor. He had always been regarded as a misfit, despite the fact no one trained harder and no one fought with more ferocity. Relentless and unorthodox inside the ring, his character outside of it proved erratic and difficult. Once he turned pro, almost no one wanted to manage him and even fewer wanted to fight him. It was so bad he had to abandon the 135 pound weight class and climb up to the super-lightweights to get a title shot. After annihilating veteran champion Antonio Cervantes in four rounds, his hometown of Cincinnati held a parade for him that was literally one car long.

The crowd in the Orange Bowl was treated to a war for the ages.

In stark contrast to Pryor, Alexis Arguello was smooth and charming, both in and out of the ring. An elder statesman and something of a legend, his class and sportsmanship was as admired as his excellent ring technique and lethal power. Boasting a devastating right hand and 62 knockouts in 72 wins, Arguello had the respect and approval of almost everyone in boxing, while the bitter Pryor charmed no one. And unlike Arguello’s refined and studied ring craft, Pryor was wild and unpredictable, constantly darting, lunging, and throwing heavy punches from any position and any angle.

Against Arguello, few thought Pryor would win. More to the point, the public wanted Alexis to succeed and make history, and the stands at the cavernous Orange Bowl in Miami filled up with thousands of Latin-Americans eager to see their hero become a superstar. But the anti-Pryor crowd didn’t bother the champion in the least. People had been tearing Aaron down and telling him he’d never amount to much all his life and he had proven them all wrong. Now he understood that defeat to Arguello would mean being quickly cast aside so more popular boxers could get the big opportunities and the big money. If Arguello was fighting for history, Pryor had an equally potent motivation: to make himself matter.

The intense and thrilling battle that took place that night has only grown in stature over the years; Pryor vs Arguello I is widely viewed as one of the greatest action fights of all time. And it was Pryor who made it a war. From the outset, “The Cincinnati Cyclone” charged at Arguello with one thing on his mind: knockout. The opening round shocked everyone as the champion immediately took Arguello out of his game plan and imposed a ferocious and fast-paced slugfest. It was an opening round to rival that of Hagler vs Hearns, Pryor throwing an amazing 130 punches, the normally patient Arguello not far behind with 108.

Thus the tone and pace of the contest were set; round after fast-paced round rushed by at breakneck speed as the two champions slugged it out. Pryor appeared to have the edge with his faster hands and relentless buzzsaw style, but Arguello’s fans never lost heart because they knew victory was just one clean right hand away. The only problem with this theory was that whenever Pryor got nailed, he just smiled and tore back in for more. Arguello regularly struck with flush overhand or straight rights that would have stunned a rhinoceros, but had little effect on the wild man from Ohio who just never stopped throwing punches.

All were amazed at the sturdiness of Pryor’s chin.

But even wild men are human, and as the bout entered the later rounds, Pryor’s kamikaze attack appeared to wind down. Behind on points and sporting cuts around the eyes, Arguello seized the initiative and began to drive the champion back with his favourite combination, a left hook to the body followed by the right hand upstairs. Rounds 11 and 12 belonged to the challenger and the crowd roared as Pryor appeared to be fading and their hero looked ready to make history. But it was not to be.

The gallant triple-crown champion made his last stand in round 13. The crowd exulted as the challenger dug deep with big left hooks to the body and then blasted Pryor with huge rights hands upstairs, one of which hit Pryor so violently it buckled his knees and had him looking straight up to the skylights above. But the determined champion simply refused to go down. At the end of the round, Alexis must have been asking himself, “What do I have to hit this guy with, a sledgehammer?” And indeed, as round 14 began, Arguello was visibly deflated and fatigued, breathing through his mouth and suddenly there to be hit.

It’s November, 1982 and the sport of boxing is bigger than ever. Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns are all mainstream stars and fight fans enjoy championship matches on free cable TV almost every weekend. Rocky III is a huge hit in theaters and just a few months previous, one of the richest fights of all-time had taken place, Larry Holmes vs. Gerry Cooney. And standing right in the thick of things, not yet a boxing superstar but certainly one of the higher profile champions: Alexis Arguello.

A regular on network television, the Nicaraguan is regarded as not only one of the best boxers on the planet, but an all-time great, only the seventh fighter in the long history of boxing to win three divisional world titles. And that’s what the big battle in Miami’s Orange Bowl was all about: to see if Arguello could make history and emerge as a true immortal, a sports superstar, by becoming the first boxer ever to win world titles in four different weight classes.

Arguello’s chief threat was his powerful right.

The man Arguello had to beat to get that fourth belt was not a household name, but everyone in the game knew Aaron “The Hawk” Pryor was one hell of a fighter. In contrast to popular champions like Leonard and Hearns, Pryor’s whole career had been a struggle for recognition. An outstanding amateur talent with over 200 wins, he dropped a close decision to Howard Davis Jr. in a critical match and so failed to make the team that won a boatload of medals at the ’76 Olympics. Without the fame a gold medal would have brought him, Pryor soon discovered the public was not particularly anxious to buy tickets to his fights.

While some might have been discouraged by this, being the outsider was nothing new for Pryor. He had always been regarded as a misfit, despite the fact no one trained harder and no one fought with more ferocity. Relentless and unorthodox inside the ring, his character outside of it proved erratic and difficult. Once he turned pro, almost no one wanted to manage him and even fewer wanted to fight him. It was so bad he had to abandon the 135 pound weight class and climb up to the super-lightweights to get a title shot. After annihilating veteran champion Antonio Cervantes in four rounds, his hometown of Cincinnati held a parade for him that was literally one car long.

The crowd in the Orange Bowl was treated to a war for the ages.

In stark contrast to Pryor, Alexis Arguello was smooth and charming, both in and out of the ring. An elder statesman and something of a legend, his class and sportsmanship was as admired as his excellent ring technique and lethal power. Boasting a devastating right hand and 62 knockouts in 72 wins, Arguello had the respect and approval of almost everyone in boxing, while the bitter Pryor charmed no one. And unlike Arguello’s refined and studied ring craft, Pryor was wild and unpredictable, constantly darting, lunging, and throwing heavy punches from any position and any angle.

Against Arguello, few thought Pryor would win. More to the point, the public wanted Alexis to succeed and make history, and the stands at the cavernous Orange Bowl in Miami filled up with thousands of Latin-Americans eager to see their hero become a superstar. But the anti-Pryor crowd didn’t bother the champion in the least. People had been tearing Aaron down and telling him he’d never amount to much all his life and he had proven them all wrong. Now he understood that defeat to Arguello would mean being quickly cast aside so more popular boxers could get the big opportunities and the big money. If Arguello was fighting for history, Pryor had an equally potent motivation: to make himself matter.

The intense and thrilling battle that took place that night has only grown in stature over the years; Pryor vs Arguello I is widely viewed as one of the greatest action fights of all time. And it was Pryor who made it a war. From the outset, “The Cincinnati Cyclone” charged at Arguello with one thing on his mind: knockout. The opening round shocked everyone as the champion immediately took Arguello out of his game plan and imposed a ferocious and fast-paced slugfest. It was an opening round to rival that of Hagler vs Hearns, Pryor throwing an amazing 130 punches, the normally patient Arguello not far behind with 108.

Thus the tone and pace of the contest were set; round after fast-paced round rushed by at breakneck speed as the two champions slugged it out. Pryor appeared to have the edge with his faster hands and relentless buzzsaw style, but Arguello’s fans never lost heart because they knew victory was just one clean right hand away. The only problem with this theory was that whenever Pryor got nailed, he just smiled and tore back in for more. Arguello regularly struck with flush overhand or straight rights that would have stunned a rhinoceros, but had little effect on the wild man from Ohio who just never stopped throwing punches.

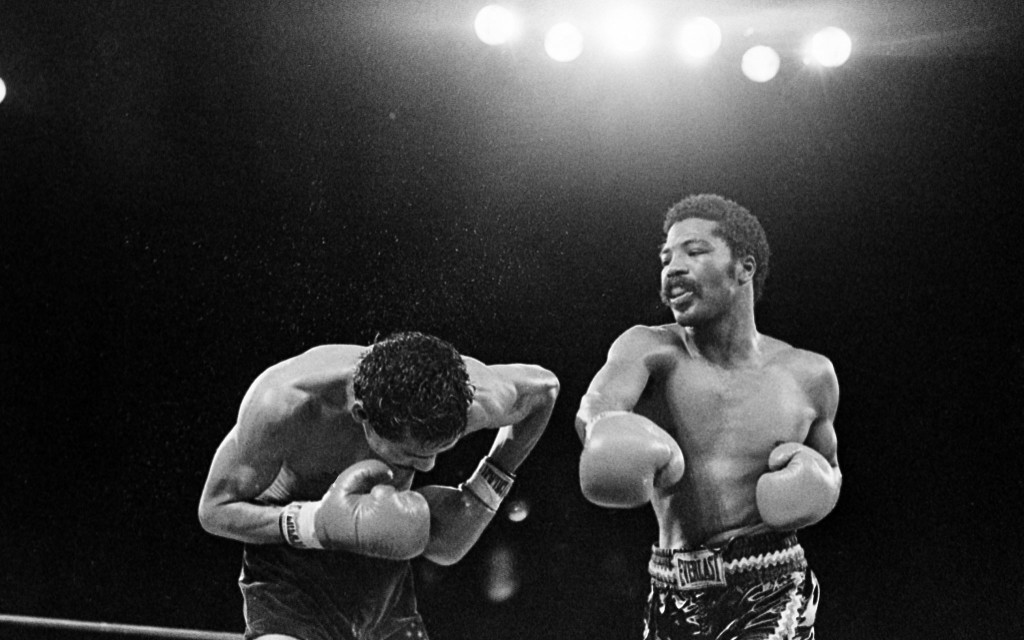

All were amazed at the sturdiness of Pryor’s chin.

But even wild men are human, and as the bout entered the later rounds, Pryor’s kamikaze attack appeared to wind down. Behind on points and sporting cuts around the eyes, Arguello seized the initiative and began to drive the champion back with his favourite combination, a left hook to the body followed by the right hand upstairs. Rounds 11 and 12 belonged to the challenger and the crowd roared as Pryor appeared to be fading and their hero looked ready to make history. But it was not to be.

The gallant triple-crown champion made his last stand in round 13. The crowd exulted as the challenger dug deep with big left hooks to the body and then blasted Pryor with huge rights hands upstairs, one of which hit Pryor so violently it buckled his knees and had him looking straight up to the skylights above. But the determined champion simply refused to go down. At the end of the round, Alexis must have been asking himself, “What do I have to hit this guy with, a sledgehammer?” And indeed, as round 14 began, Arguello was visibly deflated and fatigued, breathing through his mouth and suddenly there to be hit.

Pryor immediately took advantage. He stunned Arguello with a left, staggered him with a right, then softened him up with a series of jabs before smashing home a thunderous right hand that could have caved in a side of the Orange Bowl. Arguello’s whole body buckled and will alone kept him upright as he skittered backwards to the ropes. Pryor pounced and connected with more than a dozen flush power shots before the referee finally jumped in to stop it and Alexis crumbled to the canvas. After 14 furious rounds, Pryor had halted Arguello’s bid for fistic immortality.

And yet even this victory, the biggest of his life, the critics and detractors tried to take from Pryor. Before the final round, his trainer, Panama Lewis, later convicted of tampering with a boxer’s gloves and subsequently banned from boxing, had been overheard asking for a special water bottle, “the one [he] mixed,” and in the bout’s aftermath everyone offered up their preferred stimulant as the secret ingredient.

Aaron Pryor: Ink drawing by Damien Burton.

As if that really had anything to do with the outcome. As if Pryor needed the help of any dirty tricks to win. As if he had not clearly demonstrated that no one short of King Kong was going to beat him that night, because the champion, who had given the greatest performance of his career, knew: defeat was not an option. Or as Pryor himself put it a few days before this electrifying war that will never be forgotten: “If he loses, he’s still a champion. But if I lose it’s over. For me, it’s either $4.95 an hour or world champion. Everything’s on the line for me.” — Michael Carbert

It’s November, 1982 and the sport of boxing is bigger than ever. Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns are all mainstream stars and fight fans enjoy championship matches on free cable TV almost every weekend. Rocky III is a huge hit in theaters and just a few months previous, one of the richest fights of all-time had taken place, Larry Holmes vs. Gerry Cooney. And standing right in the thick of things, not yet a boxing superstar but certainly one of the higher profile champions: Alexis Arguello.

A regular on network television, the Nicaraguan is regarded as not only one of the best boxers on the planet, but an all-time great, only the seventh fighter in the long history of boxing to win three divisional world titles. And that’s what the big battle in Miami’s Orange Bowl was all about: to see if Arguello could make history and emerge as a true immortal, a sports superstar, by becoming the first boxer ever to win world titles in four different weight classes.

Arguello’s chief threat was his powerful right.

The man Arguello had to beat to get that fourth belt was not a household name, but everyone in the game knew Aaron “The Hawk” Pryor was one hell of a fighter. In contrast to popular champions like Leonard and Hearns, Pryor’s whole career had been a struggle for recognition. An outstanding amateur talent with over 200 wins, he dropped a close decision to Howard Davis Jr. in a critical match and so failed to make the team that won a boatload of medals at the ’76 Olympics. Without the fame a gold medal would have brought him, Pryor soon discovered the public was not particularly anxious to buy tickets to his fights.

While some might have been discouraged by this, being the outsider was nothing new for Pryor. He had always been regarded as a misfit, despite the fact no one trained harder and no one fought with more ferocity. Relentless and unorthodox inside the ring, his character outside of it proved erratic and difficult. Once he turned pro, almost no one wanted to manage him and even fewer wanted to fight him. It was so bad he had to abandon the 135 pound weight class and climb up to the super-lightweights to get a title shot. After annihilating veteran champion Antonio Cervantes in four rounds, his hometown of Cincinnati held a parade for him that was literally one car long.

The crowd in the Orange Bowl was treated to a war for the ages.

In stark contrast to Pryor, Alexis Arguello was smooth and charming, both in and out of the ring. An elder statesman and something of a legend, his class and sportsmanship was as admired as his excellent ring technique and lethal power. Boasting a devastating right hand and 62 knockouts in 72 wins, Arguello had the respect and approval of almost everyone in boxing, while the bitter Pryor charmed no one. And unlike Arguello’s refined and studied ring craft, Pryor was wild and unpredictable, constantly darting, lunging, and throwing heavy punches from any position and any angle.

Against Arguello, few thought Pryor would win. More to the point, the public wanted Alexis to succeed and make history, and the stands at the cavernous Orange Bowl in Miami filled up with thousands of Latin-Americans eager to see their hero become a superstar. But the anti-Pryor crowd didn’t bother the champion in the least. People had been tearing Aaron down and telling him he’d never amount to much all his life and he had proven them all wrong. Now he understood that defeat to Arguello would mean being quickly cast aside so more popular boxers could get the big opportunities and the big money. If Arguello was fighting for history, Pryor had an equally potent motivation: to make himself matter.

The intense and thrilling battle that took place that night has only grown in stature over the years; Pryor vs Arguello I is widely viewed as one of the greatest action fights of all time. And it was Pryor who made it a war. From the outset, “The Cincinnati Cyclone” charged at Arguello with one thing on his mind: knockout. The opening round shocked everyone as the champion immediately took Arguello out of his game plan and imposed a ferocious and fast-paced slugfest. It was an opening round to rival that of Hagler vs Hearns, Pryor throwing an amazing 130 punches, the normally patient Arguello not far behind with 108.

Thus the tone and pace of the contest were set; round after fast-paced round rushed by at breakneck speed as the two champions slugged it out. Pryor appeared to have the edge with his faster hands and relentless buzzsaw style, but Arguello’s fans never lost heart because they knew victory was just one clean right hand away. The only problem with this theory was that whenever Pryor got nailed, he just smiled and tore back in for more. Arguello regularly struck with flush overhand or straight rights that would have stunned a rhinoceros, but had little effect on the wild man from Ohio who just never stopped throwing punches.

All were amazed at the sturdiness of Pryor’s chin.

All were amazed at the sturdiness of Pryor’s chin.

But even wild men are human, and as the bout entered the later rounds, Pryor’s kamikaze attack appeared to wind down. Behind on points and sporting cuts around the eyes, Arguello seized the initiative and began to drive the champion back with his favourite combination, a left hook to the body followed by the right hand upstairs. Rounds 11 and 12 belonged to the challenger and the crowd roared as Pryor appeared to be fading and their hero looked ready to make history. But it was not to be.

The gallant triple-crown champion made his last stand in round 13. The crowd exulted as the challenger dug deep with big left hooks to the body and then blasted Pryor with huge rights hands upstairs, one of which hit Pryor so violently it buckled his knees and had him looking straight up to the skylights above. But the determined champion simply refused to go down. At the end of the round, Alexis must have been asking himself, “What do I have to hit this guy with, a sledgehammer?” And indeed, as round 14 began, Arguello was visibly deflated and fatigued, breathing through his mouth and suddenly there to be hit.

“The Hawk” never stopped attacking.

Pryor immediately took advantage. He stunned Arguello with a left, staggered him with a right, then softened him up with a series of jabs before smashing home a thunderous right hand that could have caved in a side of the Orange Bowl. Arguello’s whole body buckled and will alone kept him upright as he skittered backwards to the ropes. Pryor pounced and connected with more than a dozen flush power shots before the referee finally jumped in to stop it and Alexis crumbled to the canvas. After 14 furious rounds, Pryor had halted Arguello’s bid for fistic immortality.

And yet even this victory, the biggest of his life, the critics and detractors tried to take from Pryor. Before the final round, his trainer, Panama Lewis, later convicted of tampering with a boxer’s gloves and subsequently banned from boxing, had been overheard asking for a special water bottle, “the one [he] mixed,” and in the bout’s aftermath everyone offered up their preferred stimulant as the secret ingredient.

Aaron Pryor: Ink drawing by Damien Burton.

As if that really had anything to do with the outcome. As if Pryor needed the help of any dirty tricks to win. As if he had not clearly demonstrated that no one short of King Kong was going to beat him that night, because the champion, who had given the greatest performance of his career, knew: defeat was not an option. Or as Pryor himself put it a few days before this electrifying war that will never be forgotten: “If he loses, he’s still a champion. But if I lose it’s over. For me, it’s either $4.95 an hour or world champion. Everything’s on the line for me.” — Michael Carbert

AARON PRYORALEXIS ARGUELLOLARRY HOLMESORANGE BOWLROBERTO DURANSUGAR RAY LEONARDTHOMAS HEARNS

SHARE

Save

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

BOXIANA

BOXIANA

Nov. 26, 1914: Langford vs Wills II

BOXIANA

BOXIANA

Nov. 24, 1990: Jackson vs Graham

BOXIANA

BOXIANA

Nov. 23, 1991: Holyfield vs Cooper

3 COMMENTS

heykal says:NOVEMBER 12, 2019 AT 3:20 PM

Great write up. I am too much a fan of Alexis to not mention that, even though The Hawk may have been a bit too much for him that night, Arguello was leading on the scorecards (if memory serves) and, at this level, the smallest advantage can decide the outcome. We will never know, but this win comes definitely with an asterisk for me.REPLY

wwwortegzcom@aol.com says:NOVEMBER 13, 2019 AT 12:07 AM

Aaron cheated. There’s no debating it. Arguello won, whipped his ass. The only way Pryor could win against Arguello was by cheating. That’s it. What a great win for Arguello.REPLY

Dave says:NOVEMBER 24, 2019 AT 1:03 PM

The first fight, arguably one of the greatest fights of all time will forever be tainted by the presence of the pathogen known as Panama Lewis!

Thankfully Pryor was able to redeem himself and his legacy with an outstanding performance in the second fight.REPLY

LEAVE A REPLY

Name *

Email *

Website

LATEST NEWS

“The Bronze Bomber” Must Be Better

November 29, 2019Top 12 Heavyweight Punchers

November 28, 2019Gravity

November 27, 2019The Fight City Podcast No. 33

November 27, 2019Nov. 26, 1914: Langford vs Wills II

November 26, 2019

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)