https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2020/mar/27/isaac-chamberlain-ive-been-here-before-in-a-very-dark-place

Isaac Chamberlain: 'I’ve been here before, in a very dark place'

Donald McRae

The Brixton cruiserweight was close to hitting it big as the coronavirus crisis stopped boxing for the foreseeable future, but he is no stranger to isolation and is taking the blow in his stride

@donaldgmcrae

Fri 27 Mar 2020

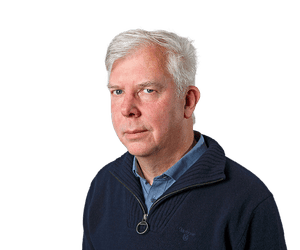

Isaac Chamberlain: ‘I honestly can’t stand the quiet whistling sound that I hear, when it’s silent in my room and it’s pitch black, as I’m writing this at 5:18am.’ Photograph: Richard Saker/The Guardian

Isaac Chamberlain: ‘I honestly can’t stand the quiet whistling sound that I hear, when it’s silent in my room and it’s pitch black, as I’m writing this at 5:18am.’ Photograph: Richard Saker/The GuardianI know I can go through hell,” Isaac Chamberlain says calmly as, rather than making his comeback on Saturday night in a fight that had offered him so much hope, the most interesting boxer in Britain settles back into another testing period of isolation. “I’ve sacrificed so much it’s got to the point that it’s become normal to me to go through these trials and tribulations. The world is in a very tough place right now but I just think: ‘I’ve been here before, in a very dark place. This is how my life has been for a long time.”

Chamberlain’s latest spell of solitude has been enforced by coronavirus, which led to the inevitable cancellation of Saturday’s bill in Coventry. His return was meant to be screened live on Channel 5. A second fight, on 25 April in London, has also been abandoned and so the Brixton cruiserweight has been consigned again to the wilderness.

Seventeen months have passed sinc Chamberlain’s last bout, a victory over Luke Watkins that helped ease the pain of his only defeat in the ring, on points to his bitter rival Lawrence Okolie in February 2018. His comeback has been derailed by a series of disasters. A family member stole £10,000 from his O2-headlining purse for fighting Okolie while subsequent fights in America were cancelled and Chamberlain was let down by jailed promoters and wayward trainers.

The boxer has spent much of the past four months in a brutal Miami training camp, from where he has written regularly to me about his struggle to cope. When we first met in person, in November, Chamberlain emerged as a vibrant and engaging character who is also capable of deep introspection. He writes long and riveting insights into his psychology that sometimes left me worrying about his mental health. But he reassured me that writing is a way of controlling his torment.

“It just makes me feel better, bro,” he told me, “and I like to write.”

I still found it striking that a boxer, who had once been an 11-year-old coerced into carrying drugs in south London while boys just a little older than him were stabbed to death, wrote with such sensitivity and eloquence.

“Hell is a perception,” Chamberlain wrote last November. “Or perhaps it’s a nightmare. What’s hell to you could be mediocre to someone else. For some people fighting is hell to them. For me, inactivity has caused me more depression and made me drown in my own perception of hell … I’m not talking about the physical and what you can see. I’m talking about something much more detrimental and lingering. The hell in your mind. It makes you feel crazy to be you. I honestly can’t stand the quiet whistling sound that I hear, when it’s silent in my room and it’s pitch black, as I’m writing this at 5:18am.”

On 11 December he sent me a photo of a single bed in a stark room. “We go again,” Chamberlain wrote. “I’m in Miami now. 5,000 miles from home. Away from friends, family and loved ones. Alone. Rottweilers are barking outside. The dawn quickly turns to darkness. And reality sets in … ”

FacebookTwitterPinterest Isaac Chamberlain lands a punch on Luke Watkins on his way to victory in October 2018. Photograph: James Chance/Getty Images

Advertisement

A few weeks later, Chamberlain messaged me: “This wasn’t the 2019 I wanted, but it was character building. I’m in the ground now, buried. Sitting in my room on Christmas Day. But I will rise. Deep down an undeniable force is driving my actions. I must embrace it.”

On 4 January, after moving into a hostel in Miami, Chamberlain sent me a photograph of him in a white vest standing against a grimy bunk bed. “In prison,” he wrote.

His messages over the next eight weeks were much more cheerful. Chamberlain confirmed that he had signed a five-year deal with the British promoter Mick Hennessy, who steered Carl Froch and Tyson Fury to their first world titles. His upbeat mood continued as he spoke enthusiastically about how much it would mean to be back in the ring again. When I texted him news of my plan to write about him for the Guardian he replied: ‘Amazing my brooooooo … ”

But then, on 17 March, he attached the official news that both his fights were off and that there would be no boxing for many months. Chamberlain is back in Britain but, as the lockdown intensifies, we have to do this interview remotely. I can hear the breath catch in his throat when I ask how he felt after he received the crushing, if hardly surprising, news. “I was fighting back tears on the train, trying not to show anyone I was so upset. I was thinking, ‘What more do I need to do? Why, just when I have my big break, does this happen?’ But almost straightaway I told myself, ‘Let’s not be selfish here. The coronavirus is affecting everyone. It’s bigger than me. Other people are suffering more than me.’”

Chamberlain sighs. “But you’re fighting with your mind because you think how different it should have been. In my last week of sparring I was knocking guys out. I was that ready I was knocking guys out with 20oz gloves. I was destroying them.”

He had been meant to spar in Miami against Yuniel Dorticos, the Cuban IBF world champion. “I didn’t in the end,” he says. “I sparred one of his guys and lit him up. That put them off. They want to have spars that build the fighter’s confidence. I respect that. I get that. They’re not going to want this crazy, hungry, young kid from London destroying Dorticos’s confidence. I would have lit him up, 100%. So they would say to me, ‘No sparring today’ or ‘He’s not feeling so well.’”

Russian boxers post videos that appear to flout self-isolation rules

Read more

The 26-year-old seems much more philosophical than I had expected him to be after another big setback. “How can I stop when I’ve got this far? It’s also been better because Mick Hennessy and his team are such great guys. I can talk to them and I never had that sort of relationship with [Eddie Hearn’s] Matchroom. They really appreciate me and I have a lot of love for them because of the way they’ve treated me.

Advertisement

“Before, I was going through so much shit on my own. Now I have these people around me, consoling me, saying, ‘Don’t worry, Isaac. We’ve got you. It’s going to be OK.’ It feels good for someone else to pick you up. It’s not me picking myself up all the time.

“I also still feel really excited about the Hennessy deal. All their shows are free-to-air TV. There’s a gap in the market because you can utilise that free audience of about three million viewers on average. Imagine if I turn it into four or five million viewers? That would be massive. I’m charismatic. I can talk. I can fight. People were coming to see me because I was starting to sell both venues out.”

When does Hennessy expect boxing to resume? “He said: ‘I’ve spoken to some very important people. I think the next show will probably be in September.’ I thought, ‘Fucking hell …. six months.’ But then I calmed down. I just need to keep in good shape. It was so hard in Miami, so it’s time for a little rest.”

Chamberlain seems better equipped than many people to adjust to the lockdown. “Everyone is talking about isolation and how they’re struggling. Well, I’ve been isolated in Miami for months. I was isolated from hope or any guarantee. It was hard but I got through it. I remember when I came back from Miami the time before this one I was so weak. I hadn’t spoken to anyone for so long. I was really isolated. When people recognised me and friends spoke to me I thought, ‘Oh, crap.’ Now it’s different.”

Chamberlain is cushioned by his Hennessy contract and also by the sponsorship he receives from the TCA clothing line. Another company, Vonder Europe, have provided an apartment for him in north London during the lockdown. But he will not be immune to the uncertainty of the coming months. “100%,” Chamberlain says. “But I’ve been very poor before. Even when it was tough in Miami I dealt with those conditions. If all my money went, it wouldn’t be the end of the world. I’d find a way.”

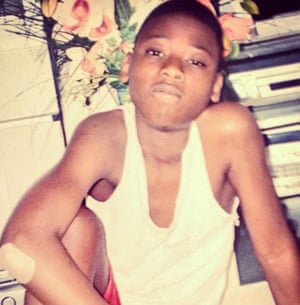

FacebookTwitterPinterest Isaac Chamberlain, at age twelve, escaped Brixton’s gangs and drugs and was saved by boxing.

Advertisement

Boxing has already been his salvation. “I got into boxing when I was about 11,” he remembers. “Around then I was still dabbling inside that street life where I was being manipulated [into delivering drugs] by older guys.

“We grew up in Brixton and my cousin, Alex Mulumba, got stabbed in the heart after he’d passed his GCSEs. It was a very sad time for the family. My mum brought me to the boxing gym because she didn’t want me going down that road. I had started to become a product of the environment, hanging around those types of people. A lot of my friends from that time are dead or in prison on life sentences.

“As soon as I got into the gym, it was euphoria. I was like, ‘What is this? People hitting each other. This stuff is normal?’ It was crazy, the sweaty gym walls and the stinky gloves. I loved it. I would be in there all day, every day. I’m the type of person, especially as a kid, that if I liked something I would be obsessed with it. I’m still like that. I’ll just keep training hard even though I wouldn’t know where my career was going.

“The thing I loved most about boxing was that it lifted me up. I’d never had those words of encouragement. People were saying, ‘You could be a champion.’ I was like, ‘Shit, these people think I can be something.’ I’d never had that from teachers, not from my mum, not from anyone. I kept coming back so I could hear those words again because it felt so good. So boxing saved my life, bigwant is the WBC one. It’s beautiful and it’s my phone wallpaper. I look at it when I wake up and before I go to sleep. The current champion is Ilunga Makabu, from the Congo, and if we fight I’ll destroy him. The cruiserweights out there are getting old and I don’t think they’re that good.”

On Chamberlain’s Twitter masthead it says “The Path To Paradise Is Through Hell”.

He laughs softly and then, as is his way, Chamberlain offers fresh hope all over again. “It’s true. Whatever you’re going through, you can get past it. If you feel you’re in hell right now, why would you stay there? That’s why it’s very important to keep going and keep pushing, no matter what life throws at you. That’s exactly what I’m doing. Keep working, keep believing, and you will come through it. I’m a living testament to that. We can all get through this time.”

https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2020/mar/27/isaac-chamberlain-ive-been-here-before-in-a-very-dark-place

No comments:

Post a Comment