Newsletters

NEWS

SF Gate

BAY AREA & STATE

By Charles Burress,

Chronicle Staff Writer

Dec 8, 2003

What happens when you cross the ivory tower with the school of hard knocks?

You get a slight, bespectacled and seemingly mild-mannered UC Berkeley professor named Loïc Wacquant, also known as "the boxing sociologist" to his peers and as fast-punching "Busy Louie" to his boxing-gym buddies from the cutthroat South Side ghetto of Chicago.

He may be the only man on the planet who fought in the famous Golden Gloves competition and writes books quoting heavy-duty French intellectuals in company with Karl Marx, Muhammad Ali and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

The outgoing, French-born Wacquant (pronounced Vah-kan) is an energetic, loquacious man of passion with little taste for lassitude. To study boxing, he became a boxer -- not a dilettante token boxer -- but a full-time, sweating, battered, bruised and highly trained pugilist who devoted three and half years to perfecting the craft.

And what fate did the ring have in store for the 137-pound, 5-foot 8-inch, self-described "young Frenchman who'd just arrived from a small village in Southern France"?

The answer comes in a new book, published somewhat belatedly 15 years after he began his journey into the "sweet science of bruising." He recalls his impression on first seeing his opponent just before the Golden Gloves bout, his first and only official fight:

"Damn, he's a tall black guy with the musculature of a panther. He must be a good six foot one, with long arms, supple like vines."

The bell rings, the fighters trade punches and then "suddenly, boom! Everything swings upside down, the ring pitches wildly, the ceiling lights blind me and ... the next thing I know, I'm on my ass on the floor. I feel like a grenade exploded right in my face! I didn't see anything coming."

But with the combative spirit that has also fueled his sometimes brutal academic battles, Wacquant sprang back up and ended the bout with a barrage of punches against his retreating opponent. His coach and fellow fighters from the Woodlawn Boys Club gym swore he'd won, but he lost on a judges' decision.

Despite waking up the next day with the bridge of his nose swollen to twice its size and much of his face looking like pummeled eggplant, he was hooked on the sport. He said he even decided at one point to chuck his academic career for professional prizefighting.

Not only had he been transformed by the emotional ties with the other fighters forged by collective sacrifice and training and especially by the father-son bond that he'd formed with his coach, DeeDee Armour. He also found it nearly impossible to regain the distance needed to write about his experience as a professional ethnologist.

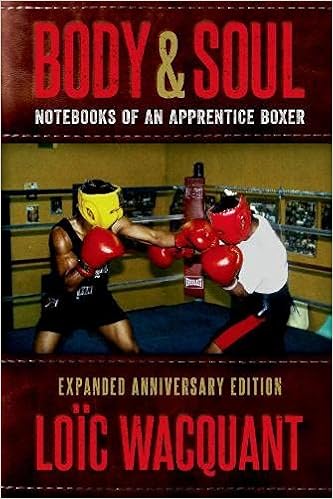

It took nearly a decade for him to write his book, "Body & Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer," just released by Oxford University Press. (It first appeared in French in 2001.)

Remarkably, his plunge into extreme participant observation began without his intending it.

In Aug. 1988, when he first walked into the dimly lit, odor-rich Chicago gym that was to become his home, he had no idea that he would try boxing himself. He was a 27-year-old doctoral student at the University of Chicago, looking for a way to study the black ghetto.

"If you'd told me then, 'One day you're going to box,' I would have said, 'Look, I'm more likely to go on the next space shuttle and walk on the moon,' " the now 43-year-old Wacquant said in an interview.

But once inside the gym he quickly saw that "there was no role whereby I could sit on a chair and observe and talk to people like a fly on the wall," he said.

So when the old coach, Armour, asked, "Well, what do you want to do?," Wacquant uttered the words that would drastically alter his future.

"I said, 'Well, um, I'd like to learn how to box,' which wasn't my intention at all."

In a career that began with such a dramatic and colorful launch, it's perhaps no surprise that Wacquant has been crowned with some of America's most prestigious honors -- selected to Harvard's elite Society of Fellows and given a MacArthur Fellowship (called the "genius grant" by the media).

Nor was it viewed as out-of-character when he dropped something of a bomb into the normally genteel world of American social sciences last year with a scathing attack in the eminent American Journal of Sociology.

In a review of what he called the "cardboard cutouts" of three sociologists' work, he hurled what was seen as a broad indictment of the field, saying in effect that "American ethnography has tended to romanticize the people one is studying without paying attention to how people are shaped by forces outside the field-site itself," said one of his UC colleagues, sociologist Michael Burawoy.

Those he criticized took off the gloves in response. For example, Harvard's Katherine Newman, whom Wacquant accused of blind "sermonizing" and painting a false happy-face heroism on fast-food workers, charged Wacquant with "intellectual hypocrisy," "relentless distortion" and "head-in-the-sand thinking."

"Loïc has a kind of combative personality," said one distinguished sociologist, who asked not to be identified. "His pugilism is not restricted to the ring."

A disciple of the late French intellectual, Pierre Bourdieu, Wacquant comes from a leftist European background accustomed to vigorous academic criticism, the sociologist said.

Wacquant, who is leaving Berkeley after a decade to become a professor at the New School for Social Research in New York next month, takes the battles in stride.

He's focusing now on finishing his next volume, a more theoretical treatment of his research called "The Passion of the Pugilist," and bracing for what the critics will say about the just-released book.

Did he violate the ethnologists' commandment: Thou shalt not go native?

UC Berkeley emeritus sociologist Neil Smelser, who recommended the hiring of Wacquant at Berkeley, called the boxing sojourn "quite an ingenious and creative mode of ethnographic fieldwork."

Another issue likely to arise is whether Wacquant's portrait of the fighters bears the rose-tint that he attacked other scholars for.

"The big question," Burawoy said, "is whether Loïc Wacquant has done the same thing himself -- whether he has romanticized the boxers he studied."

At the least, Wacquant said he wants to usher the newly published work past the immediate gawking at the "boxing sociologist" -- one who's "white and French in a black gym" and regarded as a kind of "exotic circus animal."

His aim, he said, is not just to reveal "the very powerful, magnetic, sensuous, moral and aesthetic" forces that create boxers but also to "de- exoticize the craft" and show parallels to the sacrifice and commitment required of those who strive for excellence in other occupations.

Source:

Body and Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer (2022)

The new, expanded anniversary edition, 2022 (out in November 2021) contains 140 pages of new text sketching “the making of” the study, elaborating the theory of habitus, and charting the trials and tribulations of the gym members over 30 years and what they teach us about the economics of blood, masculinity, love, and sociology.

When French sociologist Loïc Wacquant signed up at a boxing gym in a black neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side, he had never contemplated getting close to a ring, let alone climbing into it. Yet for three years he immersed himself among local fighters, amateur and professional. He learned the Sweet science of bruising, participating in all phases of the pugilist’s strenuous preparation, from shadow-boxing drills to sparring to fighting in the Golden Gloves tournament. In this experimental ethnography of incandescent intensity, the scholar-turned-boxer fleshes out Pierre Bourdieu’s signal concept of habitus, deepening our theoretical grasp of human practice. And he supplies a model for a “carnal sociology” capable of capturing “the taste and ache of action.”

This expanded anniversary edition features a new preface and postface that take the reader behind the scenes and reveal the “making of” this classic ethnography. Wacquant reflects on his path to, and uses of, fieldwork based on apprenticeship. He traces the genealogy and draws the anatomy of habitus and explicates how he deployed it as method of inquiry. The postface retraces the trials and tribulations of his gym mates in and out of the gym over the past thirty years, and reflects on what they reveal about the economics of pain and masculinity, and the passion that binds boxers to their craft.

Body & Soul marries the analytic rigor of the sociologist with the stylistic grace of the novelist to offer a compelling portrait of a bodily craft and of life and labor in the black American ghetto at century’s end.

Source:

https://loicwacquant.org/body-and-soul-notebooks-of-an-apprentice-boxer/

No comments:

Post a Comment