.

KING OF THE RING FOR SEVEN YEARS, LARRY HOLMES WAS THE UNDISPUTED HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPION OF THE WORLD. HE'S BEEN FIGHTING FOR HIS LEGACY EVER SINCE.

by MICHAEL DOLAN

As the old proverb goes, a fool and his money are soon parted. And Larry Holmes is nobody’s fool. In the back room of Champ’s Corner, a bar and grill located within the office complex of L & D Holmes Enterprises on Larry Holmes Drive in Easton, Pennsylvania, the former undisputed heavyweight champion of the world taps away at a keyboard with the same persistent consistency as his famous left jab.

Champ’s Corner doesn’t open until 4 p.m. today. During the winter, the locals don’t venture out as often for lunch. But Holmes still comes to work just about every day and punches his own clock at his office inside the establishment. After his long time assistant, Angel, lets Holmes know that we are here, the man himself appears.

Holmes had an illustrious boxing career—48 straight victories, 20 heavyweight title defenses, seven years atop the most prestigious division in professional boxing.

“I saw on my computer the other day a picture of Floyd Mayweather,” Holmes says. “He calls himself “Money” now (laughs). He’s standing in front of a private jet he bought. A jet! And then, he has all these expensive cars lined up in front of them. About 20 of them. Now let me ask you something…” Holmes says as he gets to the punch line. “How long do you think that’s going to last? It will last until he stops fighting. And then how do you pay for all of that? The money’s gone!”

Holmes may be the most qualified person to speak on the subject of boxers and money. As he did during his reign as heavyweight champ, Holmes has managed to avoid the knockout blow to his finances that most boxers inevitably suffer. “This building that we’re sitting in right now?” Holmes says. “I paid $1.5 million to build it. And then the first week it opened, it started costing me money. Once you stop fighting, where is that money going to come from? It can’t come from your pocket anymore.”

Holmes has sold the building that we are sitting it that still hosts his name and the bar. Sold the nightclub in Easton as well. Had a house in Florida, sold that. Had a boat, sold that too. Had a fleet of 20 cars just like Mayweather, all paid in full, got rid of them all. “I may not have all the money I once did, but I don’t owe anyone anything,” Holmes says. And the same can be said about his boxing career as well.

Holmes was born in Cuthbert, Georgia, the fourth child of Flossie Holmes’ twelve children. “We were poor, man!” Holmes says of his childhood. “We had one of those houses that there was a space that you could crawl underneath. We lived like hillbillies. Water? You had to go outside and pump your water. The toilet was an outhouse outside. That’s why my father moved us here to Easton. His brothers found work up here, and so we moved.”

Holmes’ father would leave the family eventually would move to work in Connecticut to do landscaping, leaving Flossie to care for the kids.

Holmes dropped out of school in the seventh grade to work at John DiVietro’s Jet Car Wash, making a dollar an hour. “You see that bridge,” he says, pointing at the window to the view of the Easton-Phillipsburg Bridge that crosses the Delaware River into New Jersey. “I must have walked across that bridge a thousand times to shine shoes. I hit every bar on Main Street to shine shoes. There ain’t a bar or business within a five mile radius of that bridge that I did not hit to shine shoes.”

On a good day, Holmes would make $20. “But we worked from 10 in the morning until seven at night. And we walked everywhere. We didn’t have a car. And the cops were always chasing us away, because they said we weren’t allowed to do that. But we did it anyway.”

Holmes worked a variety of shift work jobs throughout his teenage years. He worked in a quarry. He drove a dump truck. He poured steel in a local mill. He even helped make artillery shells in a factory in a local factory during the Vietnam War.

When Holmes was 19, he turned his eye towards boxing. He took a job driving a truck for a pants factory so he could get steady daytime hours. Then he would train in the evenings. “Honestly, I got into it because I thought I could make so money,” he says. “I didn’t do it for fun. It was another job. I wasn’t thinking about being the heavyweight champion of the world. I was thinking about making a living.”

After winning the Golden Gloves, Holmes entered the 1972 US Olympic boxing qualifiers. In a fight against future pro, Duane Bobick, Holmes was disqualified for holding too much. “I didn’t want to go to the Olympics,” Holmes says. “Every time Bobick tried to hit me, I’d get him in a clinch. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to get hit. Well, nobody wants to get hit. But I wasn’t afraid of him. I just didn’t want to go to the Olympics. I wasn’t going to Germany. I had never been out of the country before. I had a bad feeling about the whole thing. During the fight, the referee kept saying, ‘If you hold again, I’m going to disqualify you.’ So I kept holding him. Once I got disqualified, I had this rap follow me around that I had no heart. It wasn’t that I didn’t have heart, I just didn’t want to go to the Olympics.”

After Holmes turned pro, through sheer coincidence, Muhammad Ali had acquired some land in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania and opened his training camp there. Through a mutual friend, Holmes was invited to try sparring with Ali.

“That first time, he beat me up pretty good!” Holmes says, “He gave me a black eye. They wanted to put ice on it, and I said, ‘Don’t put no ice on it! I want everyone to see this!’” Holmes came back to Easton to show his friends that he got a shiner courtesy of the champ himself. “No one believed me though,” he says. ”Not even my family. They thought I made it up. Soon I started bringing them up there to see for themselves.”

Holmes would make $1,000 a month taking his lumps from Ali. “The only reason he kept me around was because he knew I could take it,” Holmes remembers. “He told me, ‘I ain’t got time to teach anybody how to fight. I need to get ready for my fight. If you can’t take it, you’re not gonna be here.”

The day after Holmes got a black eye, he came right back to Deer Lake. And the next day. And the next. Ali quickly understood that Holmes had the heart to help him prepare for his fight and took a liking to him. He even bought him new gear to replace the falling apart headgear and gloves Holmes was using. Ali even took Holmes to spar with him in Zaire prior to his famous “Rumble in the Jungle” with George Foreman.

But Holmes’ pro career wasn’t taking off. “I wasn’t going anywhere,” he remembers. “A lot of people threw in the towel on me. They thought I didn’t have what it takes. I remember Howard Cosell saying during the Olympic trials, (as Holmes goes into his Cosell impersonation), ‘He just doesn’t have it (laughs).’ But that helped me! It motivated me to show them.”

For Holmes, sparring not only paid the bills, it set the stage for his greatness as a fighter. “See, they thought they were using me, but I was using them,” Holmes says. “I was getting an education. I was gaining confidence. I’m in there holding my own against the best heavyweights in the world. And I’m younger than them! What’s going to happen when their time is up?”

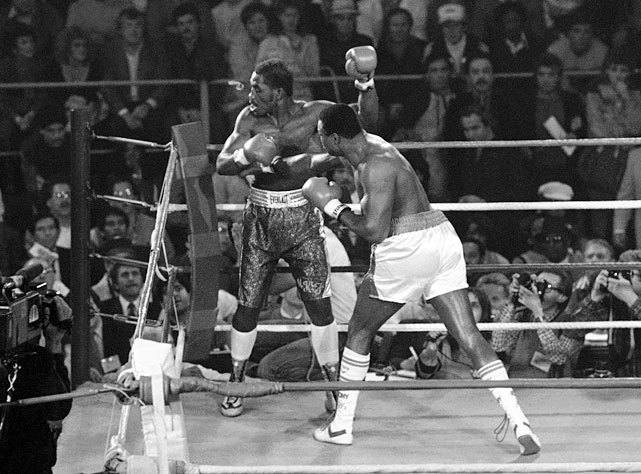

Their time was up on June 9, 1978. That’s when a 27-0 stepped into the ring at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas to face WBC heavyweight champion, Ken Norton. Norton, who had claimed the title when Leon Spinks signed to fight a rematch against Muhammad Ali, entered the ring a prohibitive favorite. Little was expected of Holmes, who most of the fight public had yet to see on the national stage.

“I wasn’t supposed to win,” Holmes says. “At least that’s what the writers thought. See this arm?” Holmes points to his left bicep. “Six days before the fight with Norton, I tore a muscle. That’s why that knot is still there. We iced it, rubbed it, iced it, rubbed it. When I got into the ring, I wasn’t even throwing my left; I was just feinting, shrugging my shoulders. I was praying. ‘Come on arm, don’t fail me now!’ After I got hit a few shots by Norton, that arm started working! I wasn’t canceling that fight. No way in hell they would have given me another chance. Opportunity only knocks once.”

That night, after a hellacious fifteen rounds, including one of the greatest fifteenth rounds in boxing history, Holmes won a split decision. He was the new heavyweight champion of the world. As he promised his friends, they all left the ring and jumped, fully clothed, into the Caesar’s Palace swimming pool. Holmes jumped in wearing his boxing trunks. After they got out of the pool, King cursed out Holmes for not going directly to the press conference. “I didn’t know, or didn’t think. But I didn’t care. I had fun doing what I wanted to do. After we went to the room, I went around to all the tables and yelled at people, ‘You fucking guys bet against me. You bet against me and I’m the heavyweight champion of the world!’ That didn’t make friends either (laughs)! But I was tired of hearing it. Imagine if your friends were telling you constantly, ‘You can’t write! You can’t even spell the words! How do you expect to write a story’”

Now, Holmes was at the center of the boxing universe. He made enough money to buy himself a house. Bought one for mom, too. Yet still, there was one currency he couldn’t seem to collect—respect.

“When I won the title, everyone thought it was a fluke,” Holmes says. “Guys right here in my hometown said, ‘That fight was fixed. Don King fixed that fight for you.’ But then I won, and won, and won, and then they had to start taking a look at me. I was starting to make money now. And I was building things here, and people thought that I was showing off with my money. When I bought this land and started building things here, people in the town liked that it was happening, but even they didn’t like that I was the one doing it, because I’m black. They loved me. They liked what I did, but I will always be black. Even though half of my family is white, I’ll always be black. I put millions of dollars into this city; do you think I get the support? Fuck no.”

“Did you ever feel like you wanted to leave,” I ask Holmes.

“I did,” he says. “I bought a house in Jacksonville and went down there for a while, but I didn’t like it. I was still boxing then, but I wasn’t boxing. Every time I needed a few dollars and didn’t want to touch the money I saved in the bank, I’d fight.”

“Now we’re working on a statue. See the sign over there?” Holmes points us to a sign across the road visible through the window. “That’s where it is supposed to go. The guy that was working on it died. My wife is taking the project over now. They named the street here after me. They had an alley that they wanted to name after me and I told them they could keep it. They didn’t have anything big enough in this city to name after me. I’m bigger than this city. So the mayor I helped gets into office. He gave me this street. But the money, the taxes I pay? They should put 10 statues up! (laughs)

Holmes takes me for a ride to a local Chinese buffet. It’s between the lunch and dinner hours, so there are only a few people in the restaurant, all of whom Holmes seems to know. If he doesn’t, he still greets them respectfully.

“I’m here!” Holmes says to the restaurant hostess. She greets him with a big hug. “Sit! Sit! Tell me what you want, and I’ll go get it.”

“You should try the buffet,” Holmes tells me. “You’re gonna love it.”

As we make our way through lunch, I share my theory with Holmes on why he never got the accolades he felt he deserved. I tell him that to sell tickets, every fight has to have a stark contrast. Good versus evil. Hero versus villain. Against Ali, Holmes was the younger man trying to vanquish a legend. Over ten rounds, Holmes brutalized an aging Ali, begging the referee to stop the fight. After it was over, he cried because of the pain he inflicted on his idol. Ali’s fans never forgave him.

Against Gerry Cooney, he was depriving a white boxing fan base of a Great White Hope. Holmes would receive death threats daily, to the point that he would do road work while carrying a gun. On the night of the fight, Vegas casinos had police snipers on the rooftops for security.

Even when he came back at age 38 to fight a young Mike Tyson (Holmes was the only fighter to fight Ali and Tyson for the championship), he was trying to short-circuit boxing, and Don King’s most electrifying attraction.

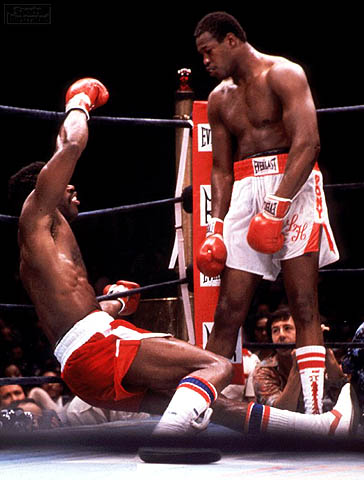

“I was off by two weeks!” Holmes says, still bristling about the Tyson fight, the only bout of Holmes’ 75-fight career that he finished with his back on the canvas. “The fight was supposed to be in June,” Holmes recalls. “Then Don moved the fight up t0 January. He had given me half the money already, so it’s hard to give the money back once you have it. So I said, ‘The hell with it. Let’s fight!’ I knew how to beat him. We were in the fourth round and he was already running out of gas. A few more rounds he would have been done. He was made for me! But my timing was off. I knew what he was going to do. He was going to throwing punches from down here because he’s short!”

Holmes demonstrates by crouching and swinging wild upward hooks. “But my timing was all off. So he caught me. BAM! BAM! And I went down. So now I’m going to set him up, make him come in and give him an upper cut. And when I reached back to throw it, my right hand got caught in the ropes. Then BAM! It was over. I wasn’t ready for the fight. I wasn’t mad at Mike or Don King. I was mad at myself for not being in shape. But I got three and a half million for it.”

The conversation turns to Don King and Holmes relationship with the dominant boxing promoter of the day.

“There were many times that Don King would say to me, ‘Here’s a million dollars but I can’t get you any more.’ Now what should I do? I can say I’m not going to take it Don. Beat it. And then what? Am I going to go back to shining shoes for $30 a day? You look at my record and you’ll see that I would fight four times a year.”

“But do you regret not negotiating differently?” I ask.

“What, I’m going to be mad at Gerry Cooney because he got $10 million and I got $10 million, even though I was the champ and he hadn’t fought anybody? You going to pay us both $10 million? Gerry, lets fight every year! We can fight every day if you want. And then I’m the fool because I should have gotten more? Meanwhile, I’m stacking those millions. I’m not going to be the dumb guy that’s going to turn the money away because it’s not enough.”

To this day, you can still feel Holmes’ survival instincts kick in. He will not be denied the legacy that he believes is rightfully his. It doesn’t matter what anyone else would do. He did it his way, and he’d do it again.

“I beat everybody they put in front of me. Then they got tired of me. They gave those decisions to Michael Spinks. (At 48-0, Holmes lost the title and his next two fights to Michael Spinks in controversial decisions.) And I knew they were never going to let me win. But then people forget. I came back and fought Ray Mercer. People were like, ‘Good luck, Larry. You’re going to need it! This guy killed Tommy Morrison.’ And I’m like. ‘Man, I’m not Tommy Morrison! I’m a pro! I was the world champion!’ And I whooped Mercer’s ass, while everyone was calling me names at ringside. I’m a bad man! And you know what else I can still do? I can talk to you today. Ali is sick. Joe Frazier’s dead. Kenny Norton’s dead. Here I am, 65 years old. I don’t owe nobody. I’m debt free. And I’m still doing what I want to do.”

Holmes has one more stop to make before we call it a day. He’s going to go visit the barbershop, so his friend Boogie can cut his hair. As we drive toward the shop, Holmes speeds up a bit. “See this curve? They call it Cemetery Curve, because the cemetery is right here.

We proceed through the curve, and you can see the gravestones peeking up from the Eastern Pennsylvania snow that blankets the entire landscape. “My whole family is buried here,” he says. “That’s why I speed up. I try not to think about it.”

We get to the barbershop and pull into the parking lot. Holmes explains how he’s even responsible for the empty space in Easton. “There used to be buildings here,” he says. “They were all run down. So I bought them and tore them down. There was no place for anyone to park around here. The city was mad as hell, but people were finally able to come out in their cars and do things in town. After a while, we built this shop on one of the lots.”

As we enter the shop, Holmes gets a hearty greeting from the patrons. “I get to cut the line, right?” Holmes barks. He’s greeted with laughs and handshakes. Even though those in line would gladly let their champ go first, he would never think of taking advantage. It’s not the right thing to do.

Holmes sits in an empty barber’s chair in the shop.

“You know Saoul Mamby?” Holmes asks.

“I do,” I say. “Tremendous fighter from New York City.”

“Yeah, he still lives in the Bronx,” Holmes says. “He and I used to train in Gleason’s Gym together in the Bronx over forty years ago. I would drive there every night and drive back home. We’ve been friends ever since. I think he’s having some trouble with dementia. He won’t stop fighting. He’ll fly over to Germany and they’ll pay him ten grand to fight somebody, so he goes.”

“How old is he,” I ask.

“I think he’s 67.”

“67?” I ask? Later I would look up Mamby’s age. He is indeed 67.

“Mamby! It’s Larry Holmes. How you feeling?”

The champ listens a bit before he interjects.

“Mamby, no more boxing! Nothing with rings and gloves and getting punched in the head, you hear? I’m going to send my friend here to do a story on what a great fighter you were.”

Holmes hangs up the phone wistfully. “I tried to convince him to move down here, but he’ll never leave the Bronx,” he says.

Holmes turns to a high school junior waiting to have his hair cut who proudly wears his Easton Football jacket.

“Son, when you play, don’t use your head to tackle people. What position do you play?”

“Defensive tackle, Mr. Holmes.”

“That’s the position that I used to play before I started boxing!” Holmes says. “Early in my life, I learned very quickly that you don’t take the punches to show how tough you are,” he says. “If you keep getting hit in the head, something’s got to give. Whenever you hear someone saying that a fighter isn’t tough enough because they don’t take punches, they’re usually standing outside the ring.”

Holmes takes photos with the young football player and asks about his season, before he’s ready to step in the chair. He points to a building across the street.

“That’s where the club was. I bought that building and refurbished it. I sold it though. Then we built this building here, and now Boogie cuts everyone’s hair here. I sold most of these place now.”

“Whatever you do, keep Boogie here!” an older man currently sitting in the barber chair says. Everyone in the shop laughs.

Eventually, Holmes settles in the chair. “Hurry up, Boogie. I’ve got to get this guy to the bus,” he says, pointing to me. “Otherwise, he’s here for the night!” After a nice trim, Holmes pays and tips generously. He shakes everyone’s hand and wishes everyone well before we head out into the night.

As we leave the shop and head to Holmes’ car, a voice calls out. “The great Larry Holmes!” a young white college-age man says as we pass. “Mr. Holmes, can I ask you something,” the young man says. “Can you spare a dollar?”

“What are you going to do with it,” Holmes asks.

“I’m going to buy a cigarette,” the young man says.

“And then what?” Holmes asks.

“I’m not sure,” the young man says.

“That’s what I’m worried about,” Holmes says, peeling off a dollar and handing it over. “Stay warm tonight.”

We get into the car for a brief ride to the bus terminal. Holmes didn’t want me to get lost or walk over in the cold. “Don’t worry,” he says. “If you miss the bus, I’ll drive you back to New York.” Even though we’ve only known each other for five hours, I have no doubt that Holmes means what he says. He always does.

TAGS: LARRY HOLMES BOXING HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMP HALL OF FAME

'via Blog this'

1 comment:

Discover how 1,000's of people like YOU are working for a LIVING online and are living their dreams right NOW.

Get daily ideas and instructions for making THOUSAND OF DOLLARS per day FROM HOME for FREE.

GET FREE ACCESS TODAY

Post a Comment